On Jan. 1, 2015, there were 1,345 alternative mutual funds in existence. Those funds followed approaches that utilized hedging, shorting, or trend-following, and sported names with terms like “multi-alternative,” “market-neutral,” and “absolute return,” among others.

Guess how many of those alternative funds still exist? 341. The other 1,000 or so have been liquidated or merged away, a 75% mortality rate. To give a fuller view, here’s the number of alternative funds that survived or died by year of inception going back to 2006.

Not surprisingly, the death rate is higher the further back you look. But whether the fund launched around the time of the global financial crisis or in the years that followed, we’ve seen a lot of these strategies come and go.

As fund companies race to bring fee-rich private equity and debt strategies to the masses, I think the binge-purge pattern we’ve seen with liquid alternative funds holds three key lessons for investors.

- The more rhapsodic the sales pitch, the more you should plug your ears

A decade or so ago, fund companies gushed about liquid alternatives’ ability to act as shock absorbers that traditional asset allocations were said to lack. The old way was passé, we were told, with alternative investments opening new pathways for retail investors to build more resilient portfolios. Here’s a representative example:

“Over the past five years, asset classes have become increasingly correlated. We believe that traditional diversification approaches may not provide an effective or consistent enough “shock absorber” to ease many investors’ qualms. In our opinion, there is no question that investors and advisors who want to improve portfolio stability should consider “diversifying harder” – that is, expanding their investment universe into new areas via alternative investment strategies.”

– “New Choices for New Alternatives: The Case for Liquid Alternatives Implementation”; Envestnet PMC; Dec. 2012

That was then and the hype was just that—hype. But you can hear echoes of it in fund firms’ campaign to “unlock access to private markets.” Now, as then, there’s talk of “democratizing” these areas and heaping superlatives on the asset class’ potential to further diversify and enhance risk-adjusted returns.

Maybe the push to make private markets more widely accessible will accrue to individual investors’ benefit. But when you consider the higher fees and greater complexity (including illiquidity) such investments entail, the onus ought to be on the seller to make a convincing case, backed up by practical, real-world results they’ve been able to generate for investors like you and me.

Until then, tune it out.

- The more action there is in an area, the wider a berth you ought to give it

The chart above makes it clear that fund companies got a little carried away launching liquid alternative funds a decade or so ago. For instance, they brought out 302 new alternative mutual funds in 2014 alone, of which only 54 still exist, the lion’s share having been mothballed within five years of inception.

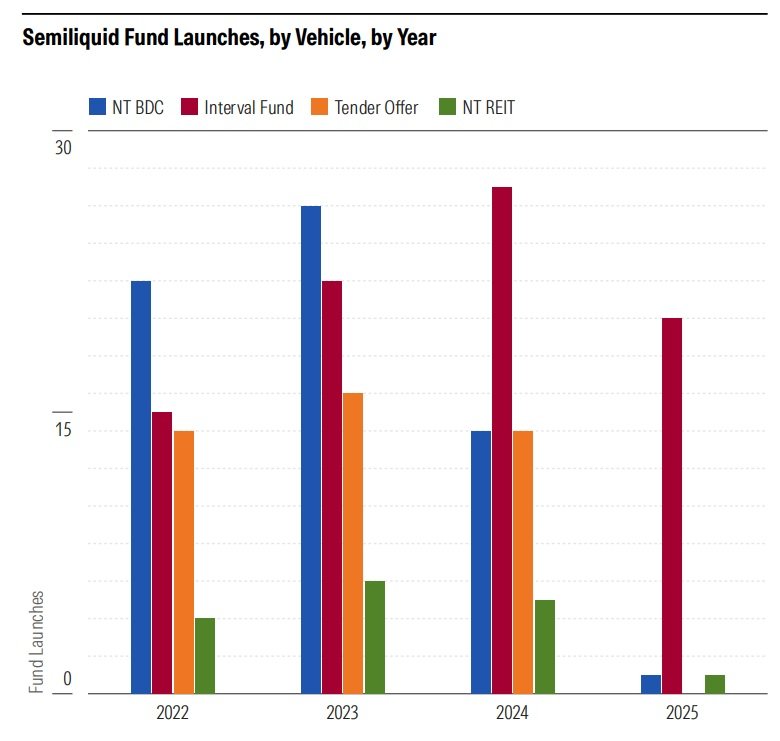

You’re seeing shades of the same thing in the semiliquid fund area, where firms have rushed to launch scores of tender offer funds, interval funds, and business development companies in recent years. My colleagues have done a good job chronicling that growth, with the chart below taken from their recent “State of Semiliquid Funds 2025” report.

Unlike liquid alternative mutual funds, we don’t have to worry about semiliquid vehicles being liquidated or merged away. They’re evergreen, allowing investors to buy when they want but limiting how much they can withdraw, which ensures the fund retains a critical mass of assets and mitigates failure risk.

But even if the funds survive, there’s still the matter of future performance. After all, the frenzy to launch alternative mutual funds came just as hedge fund performance was starting to ebb.

To illustrate, this chart compares the rolling 60-month risk-adjusted returns (for example, Sharpe ratio) of a popular hedge fund index versus the US 60% stocks/40% bonds mix. I’ve overlaid the number of alternative mutual funds that were launched in the 12 months that immediately followed a rolling 60-month period.

The pattern is clear: The hedge fund index crushed the 60/40 mix in the runup to the financial crisis, fund companies responded by launching a bevy of alternative mutual funds, and almost on cue the 60/40 allocation pulled ahead.

Private market funds need not meet the same fate. As I’ve previously written, there’s reason to expect private fund returns to vary widely, and so performance won’t necessarily be monolithic. Nevertheless, it argues for making discretion the better part of valor and tempering expectations.

- The more enticing the payoff, the deeper you ought to dig

One of the big selling points for private investments is their potential to generate strong risk-adjusted returns—for example, a handsome return without excessive volatility.

How do they manage to do that? To be sure, there’s plenty of talent, resources, and other advantages these managers bring to bear. But it’s also at least partly a function of their ability to deploy capital deliberately, hold on to investments for an extended period, and mark positions intermittently, smoothing returns in the process.

The key to this: Locking investors up. In private investments, you’re typically committing your capital for years, with certain exceptions duly noted (such as the “interval” funds I mentioned earlier).

Here again our history with alternative mutual funds can be instructive: From Jan. 1, 2009, through Dec. 31, 2014, investors poured $117 billion of assets into such funds. But in the years that followed, many investors headed for the hills in the wake of disappointing performance.

Investors were clearly taken with these funds’ low correlation with the broader market or, to put it more plainly, the way they could avoid going kerplunk when stocks and bonds went in the tank. But that overlooked the underlying process that could yield such results, an approach that made the funds likely to lag when markets took off. That’s exactly what happened. And as that unfolded, many investors bailed. (Our research has found that this left investors in alternative funds with dismal dollar-weighted returns.)

With private investments, bailing likely won’t be an option. And so if those assets are needed for some other purpose, or buyer’s remorse sets in, then the money is going to have to come from another available source, such as other allocations that are publicly traded stocks and bonds.

The point is that surface appeal doesn’t cut it. Alternative mutual fund investors were at least able to extract themselves from those holdings if they found them unsuitable or otherwise wanting. But investors in private funds won’t have that option, making it even more critical that they dig deep to understand how the underlying investment approach confers the risk/reward profile being touted and the trade-offs that entails.

Switched On

Here are other things I’m reading, listening to, or watching:

- Seth Klarman, Cliff Asness, and Kent Daniel on the Value Investing With Legends podcast

- More Cliff Asness: Christine Benz and Dan Lefkovitz sat down with the legendary quant investor on The Long View podcast

- A tour de force of modern banking with Jamie Dimon on the Acquired podcast

- Jason Zweig goes in on a couple of interval funds that refuse to face the valuation music

- “At the hearing, Lykos admitted that when the proctor stated that she needed to photograph his hand, he began licking and rubbing his fingers to prevent her from seeing the writing between his fingers”: One of the more entertaining enforcement actions I’ve read in a while

- The misunderstood impresario: Peter Guralnick discusses his new book about Elvis’ longtime manager, Colonel Tom Parker

- Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir

- “Reuters (2006 Remastered Version)” by Wire

Don’t Be a Stranger

I love hearing from you. Have some feedback? An angle for an article? Email me at jeffrey.ptak@morningstar.com. If you’re so inclined, you can also follow me on Twitter/X at @syouth1, and I do some odds-and-ends writing on a Substack called Basis Pointing.