The role of bonds in DIY investor portfolios has changed over time. While they once existed as safe assets or ballast, they have offered less in the way of stability over recent years. The interest rate rises seen since 2021 mean government bonds at least offer decent levels of income again. But with rate-hiking cycles potentially ending next year, and fiscal positions still under scrutiny, the path ahead is unclear.

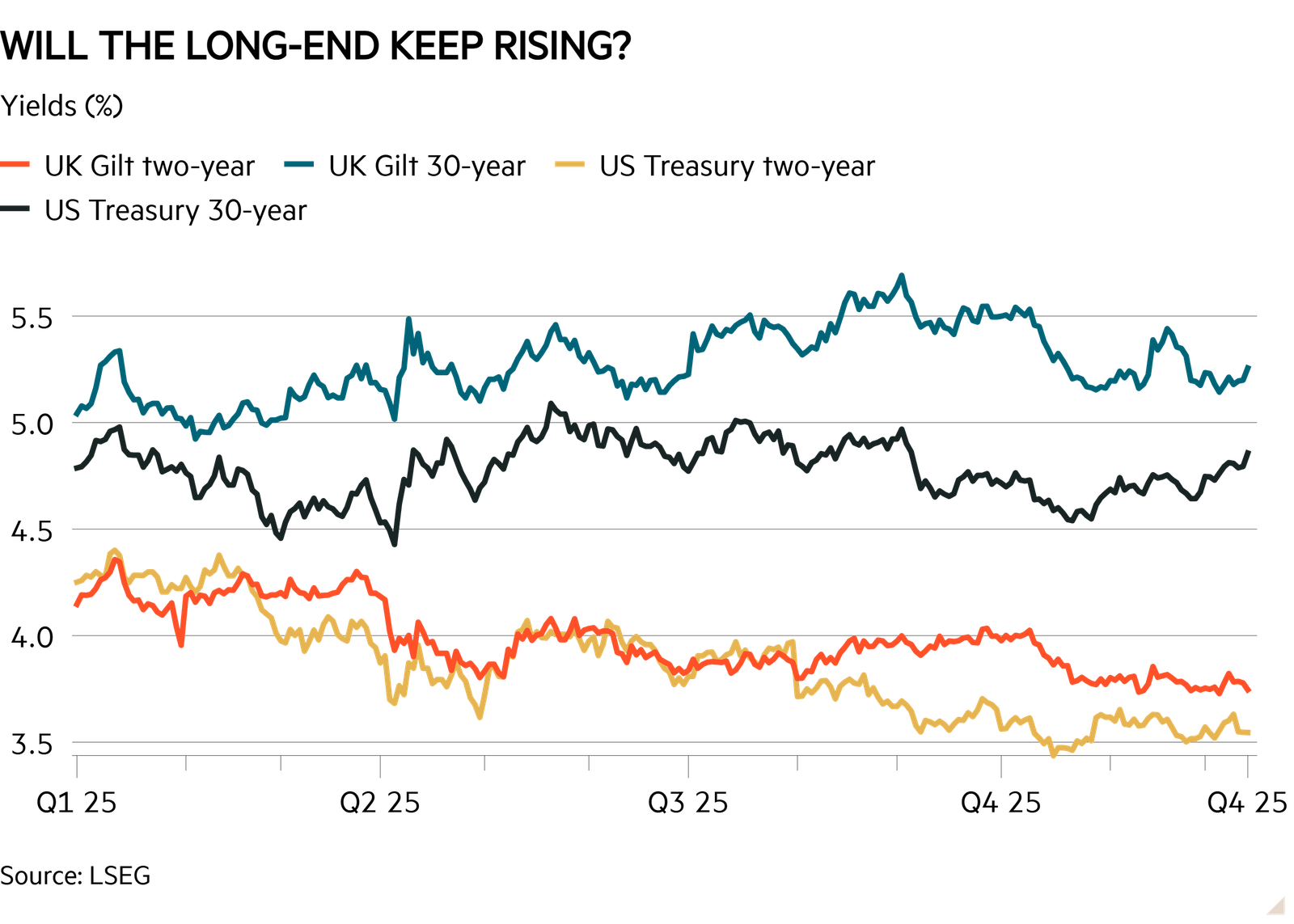

Bonds of different maturities illustrate different aspects of this puzzle. For instance, central bank rate cuts have forced yields down on shorter-dated government bonds (those that will mature within 0-5 years), meaning these bonds have risen in value. But prospects for future capital growth rely on the likes of the Bank of England or Federal Reserve cutting rates more than expected next year, which is far from certain.

On the flipside, the general indebtedness of Western economies shows no signs of going away, and means yields have risen at the long end (for those bonds with a maturity of 30 years or more). Therefore, investors in these riskier assets have lost capital, with the higher income on offer not always making up the difference.

The yield on 30-year UK government gilts will end the year around 20 basis points higher, at 5.26 per cent, but it has risen as high as 5.6 per cent during the year. And while bond markets are onside with the Labour government for the moment, this could swiftly change, sending prices down (and yields up). In the US, yields on long-dated US Treasury bonds will end the year roughly where they started, up just 7 basis points to 4.86 per cent. Again, though, yields breached the 5 per cent mark in the summer. With the debt-to-GDP ratio still rising, bond traders could easily become more apprehensive and continue sending prices down.

Ten-year government bonds offer a middle ground between short- and long-dated debt, which means they are influenced by both interest rates and fiscal policies. Their yields can also fall when growth expectations worsen, and vice versa. Ten-year gilt yields are ending the year only a little lower than they began it, but 10-year Treasuries have seen yields fall from close to 4.6 per cent to below 4.2 per cent.

This year has also been characterised by a closing of the gap between government bond yields and those available from corporate debt. The ‘spread’ between the two exists because companies are fundamentally riskier than developed market nations. This year, however, has seen these spreads fall to some of the tightest levels this century. The quest for higher yields, the perceived safety of the biggest corporate borrowers, and arguably the idea that megacap companies are now as safe if not more so than indebted nations are all factors at play. But this does leave the corporate bond sector’s prospects slightly mixed for 2026.

Mike Riddell, manager of Fidelity Strategic Bond (GB00B469J896), says he expects these spreads to stay tight given the steady global economy, low corporate issuance and high government debt issuance. However, this means that corporate bonds issued in developed markets look expensive.

So, where are the opportunities?

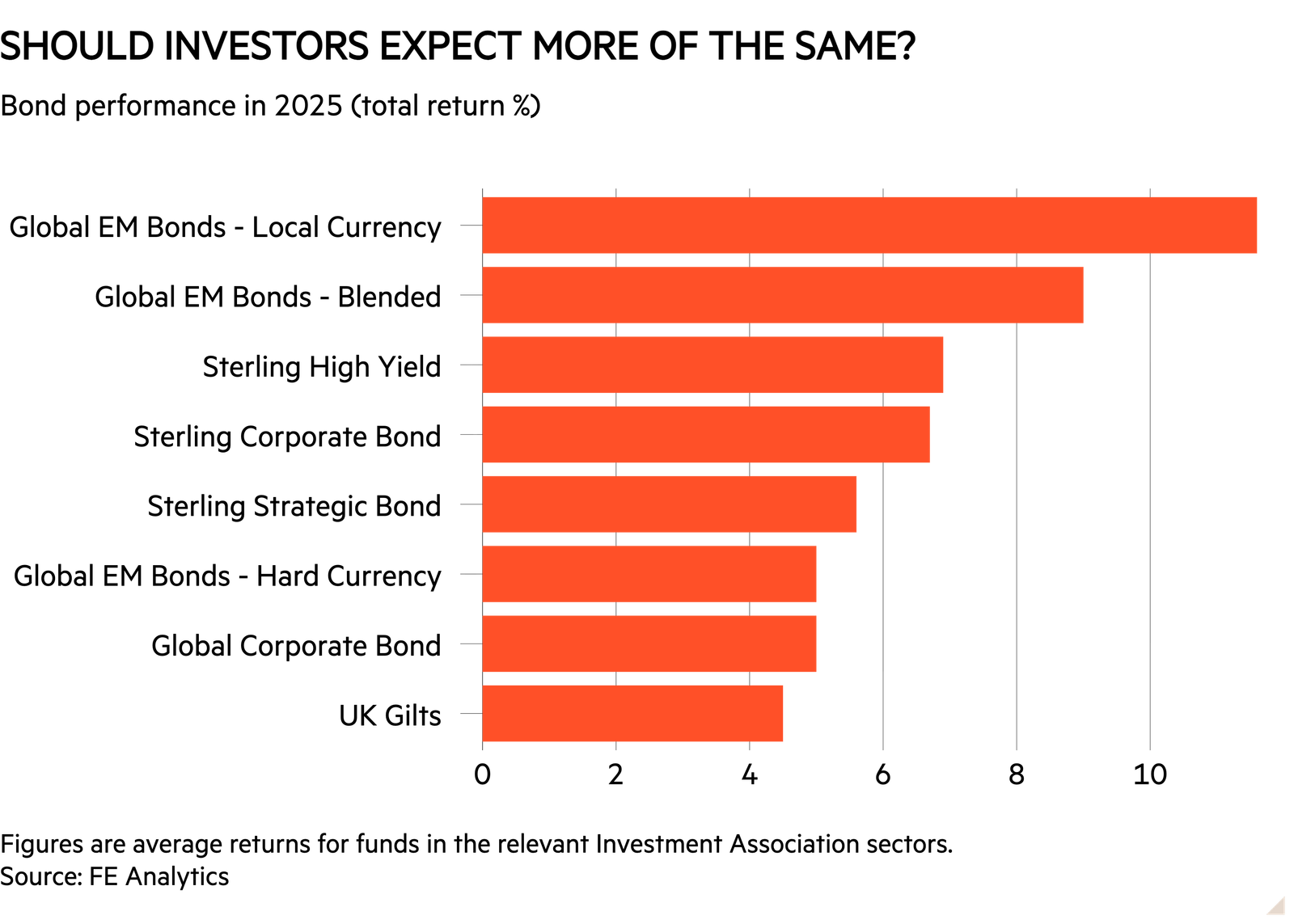

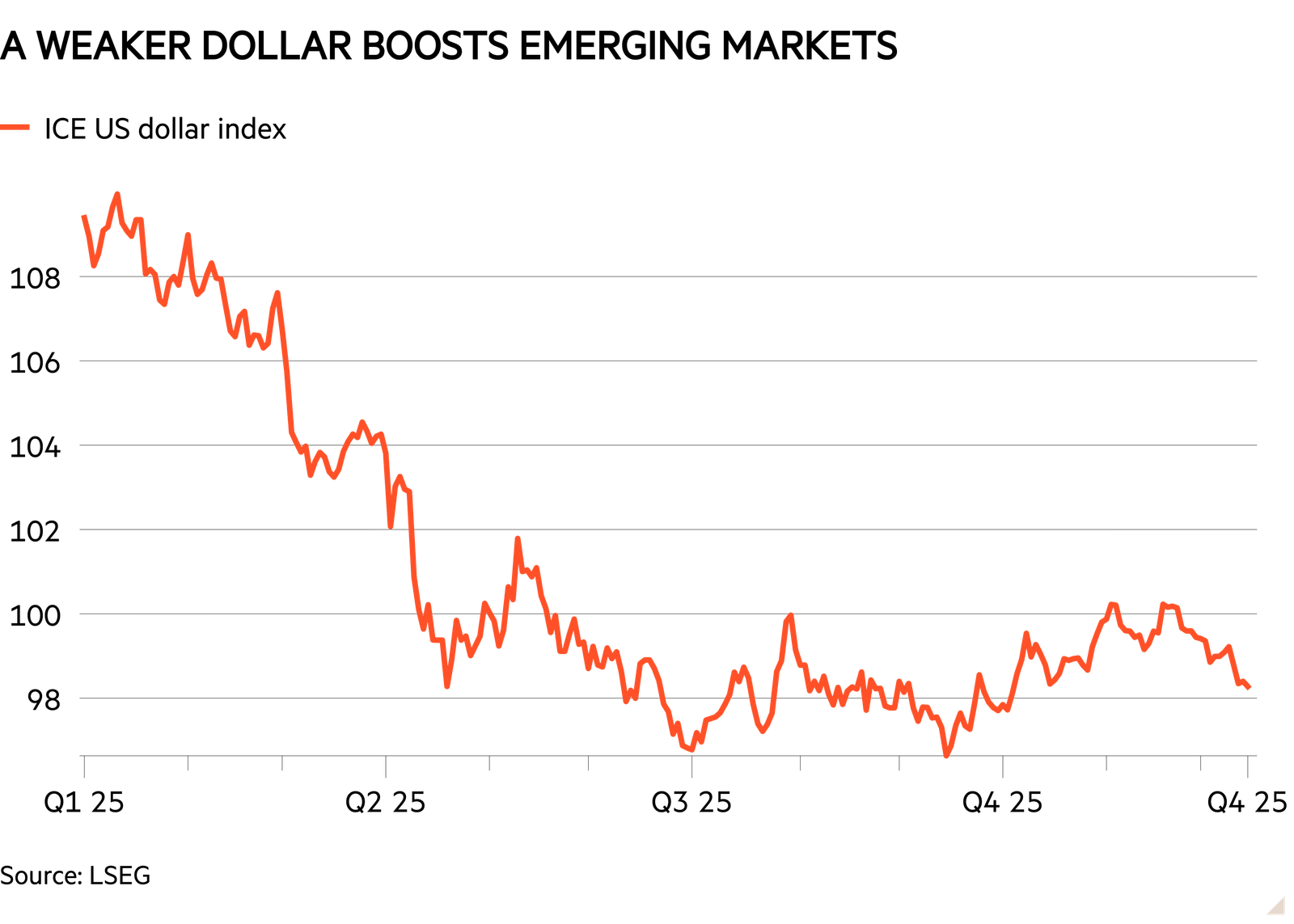

As the chart above shows, investors may need to be more open-minded and risk tolerant in 2026. Bond markets are complex and have several factors that can affect the direction of prices and yields. Currencies are often an under-appreciated one, and this year’s weakening US dollar has been a boon for emerging market bonds, particularly those priced in local currencies. The asset class is also benefiting from better economic conditions.

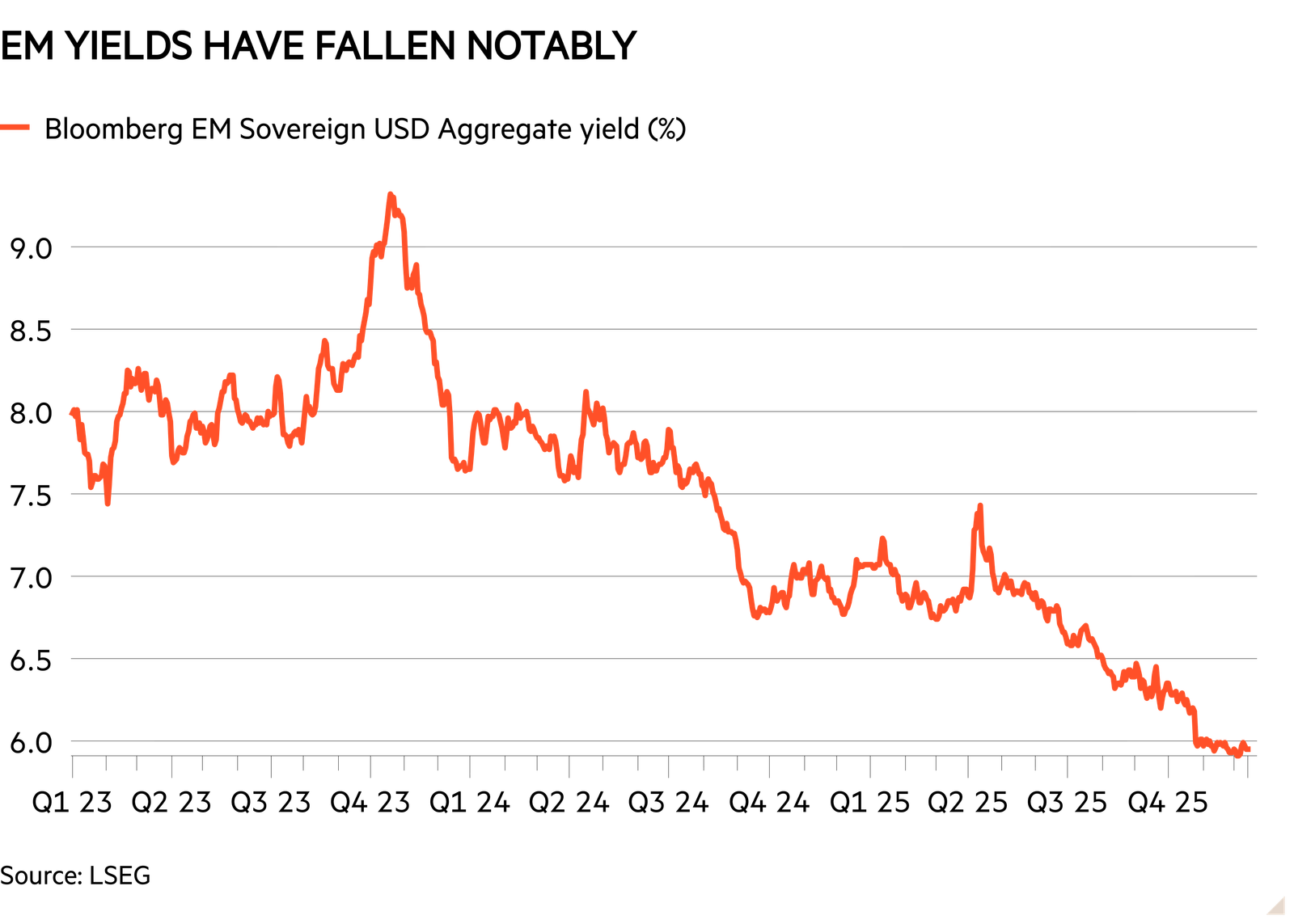

Emerging market bonds remain riskier propositions than those issued by the likes of the UK and US, but some fund managers think currency trends can help them continue to perform well next year.

Riddell says. “Some of the biggest opportunities are in currencies right now, for the funds that can take advantage. We’re big bears of the pound, where on a trade-weighted inflation-adjusted basis, sterling is not far off the strongest since the referendum. We’re also bearish on the dollar, where despite the weakening this year, it is still at the strongest levels since the mid-1980s.

“We’re positioned for a reasonable global growth outcome, and a weaker US dollar, and emerging markets are usually the biggest beneficiaries of this regime. There is a much better risk-reward trade within global bonds for investors prepared to go a little down the credit risk spectrum – particularly emerging market local currency sovereign bonds.”

Yields on both local and dollar-denominated bonds are coming down (meaning prices are rising), but there’s still room for investors to take advantage. Paul Diggle, chief economist at Aberdeen, says credit fundamentals in emerging markets are “broadly sound” and that more rate cuts from central banks, particularly the Federal Reserve, will help. “Market technicals are supportive following a period of low issuance and strong demand for local currency emerging market bonds. While the yield spread [between emerging market and safer bonds] is tight, momentum remains attractive.”

How to invest

Dedicated funds invest in local currency emerging market debt, but given the niche nature of the investment, allocations should be small, and made as part of a balanced portfolio. Some of the best-performing funds in recent years include Barings Emerging Markets Local Debt (IE00BG36V369), Pimco GIS Emerging Local Bond (IE00B2R8DW33) and MFS Meridian Emerging Markets Debt Local Currency (LU1164707306).

Ben Yearsley, investment director at Fairview Investing, also recommends Capital Group Global High Income Opportunities (LU0817816480), which often has a 50-50 split between emerging and developed markets, meaning it is a slightly more balanced play.

Of course, if the global economy takes a turn for the worse, investors would be wise to have some safer holdings or bond funds that can be more flexible. The latter, known as strategic bond funds, are particularly useful for those who want more esoteric opportunities but would rather not make big individual calls or might not know when to move.

Riddell says his Fidelity fund would move into local currency emerging market debt to “generate alpha” where possible. However, 80 per cent of the fund must be in sterling assets, so any exposure would be limited. “If we start to see evidence of a global growth slowdown, then we’d likely buy more safe-haven government bonds, and lighten up on riskier assets, including emerging markets,” he adds.

Other strategic bond funds we like include TwentyFour Dynamic Bond (GB00B5VRV677), which is part of our Top 50 Funds best-buy list; however, this tends not to stray into local currency emerging markets.

Where not to invest

Some managers are turning against corporate bonds as they no longer offer much opportunity for capital growth, yields are not high enough relative to government bonds to look enticing, and there are better opportunities elsewhere, such as the aforementioned emerging markets.

David Coombs, a multi-asset manager at Rathbones, says credit spreads being where they are means future returns “could be modest”, while RBC Wealth Management’s head of fixed income Rufaro Chiriseri says that while UK corporate bonds have shrugged off fiscal concerns, she expects yields to rise next year.

Fidelity’s Riddell, similarly, is avoiding corporate debt. “We’re unlikely to add to any corporate bonds unless we see a material revaluation along the lines of what we briefly saw around “liberation day” – with corporate bond spreads so tight, it feels like there is almost no upside, and only downside if anything goes wrong with the global economy.”

Regardless of the outlook, there tends to always be a case for owning safe havens such as UK gilts and US Treasuries, given their ability to act as insurance when the going gets tough. However, Coombs says it’s worth being wary of US Treasuries in the coming year.

“The problem, as ever, is the political landscape. Donald Trump’s tariffs could be declared illegal, which would increase the budget deficit, so fewer tariffs would become a negative, ironically,” he adds.

While many are concerned about a slowdown, some managers think there is a risk the US economy could begin to overheat next year, given tax cuts and the possibility of cheques being sent out to lower earners. “The US market might start worrying about rate hikes in 2027, and the flood of issuance makes us nervous about longer-dated US Treasuries,” Riddell adds.

What gilts can offer private investors

Gilts always offer UK investors something, even with market worries on the longer-dated end, because there are tax advantages to buying gilts directly.

The bonds are issued with a specific coupon rate, or interest rate if you prefer, and pay that interest twice a year. And, at a specific point in the future, the bond is redeemed at par, normally £1 (or £100). In the intervening period, the price of the gilt fluctuates similarly to a share price, and this is where it gets interesting for private investors.

Any capital gain made on gilts is tax-free. So if you buy a gilt that trades at £90 and redeem it at £100, that £10 of profit is free of capital gains tax (CGT). It does not need declaring on your tax return and does not count towards your annual £3,000 CGT allowance. The actual income is still taxable, but the capital growth is not.

Given the Bank of England base rate was 0.5 per cent or lower for much of the past 15 years, many gilts were issued with coupons offering rates in and around this level, and some still have plenty of years until maturity.

When base rates rose from 0.25 per cent to 5 per cent in a very short space of time between 2021 and 2023, gilts with lower coupons fell massively in price. This means investors have had a great opportunity to buy a risk-free asset (if held to maturity) with a largely tax-free return.

Some of these gilts are still available, but make sure you buy the correct ones. For example, there are two different gilts maturing in 2041, TG41 and T41F. The former has a coupon of 1.25 per cent and a current price of £59.74, whereas T41F has a coupon of 5.25 per cent and a price of £103.28. The yield to maturity (total return) for both is virtually identical, but one gives investors a largely tax-free return. That’s because almost all of TG41’s gains will come from capital growth, as it rises in value from £59 to £100 as the maturity date nears.

To buy, simply head to your chosen platform. You will pay dealing fees, and you’ll also have to ‘buy’ the income accrued since the last payment date.

By Ben Yearsley, investment director at Fairview Investing