What has changed?

A key highlight of the overhaul is a significant revamp of the expense ratio framework to increase transparency into the costs borne by investors. As part of this change, Sebi has renamed the existing expense ratio limits as the Base Expense Ratio (BER) and clarified that statutory and regulatory levies will no longer be included within these limits.

Levies such as the Securities Transaction Tax (STT), Commodity Transaction Tax (CTT), Goods and Services Tax (GST), Stamp Duty, Sebi fees and exchange charges will now be charged on actuals, over and above the permissible commission limits. Accordingly, the Total Expense Ratio (TER) will be calculated as the sum of the BER, brokerage costs, regulatory levies and statutory levies.

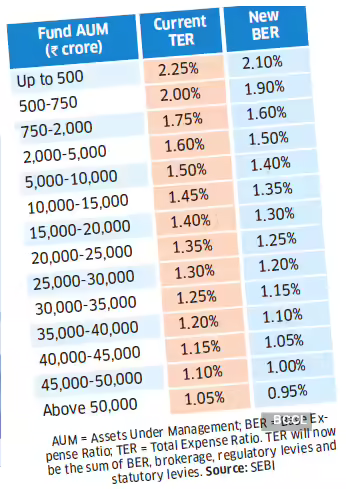

To align with this new framework, Sebi has reduced headline expense ratio ceilings across fund categories. For index funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), the BER has been lowered to 0.90% from the earlier 1%. Similar reductions have been applied to fund of funds, including those investing in liquid funds, ETFs and equityoriented schemes.

For equity-oriented schemes, the revised BER ranges from 2.10% for schemes with assets up to Rs.500 crore, to 0.95% for schemes managing assets above Rs.50,000 crore. For non-equity schemes, the revised limits range from 0.70% to 1.85% across the same asset slabs. Base expense ratios for closedended schemes have also been reduced. In addition, Sebi has rationalised brokerage limits. For cash market transactions, the brokerage cap, excluding statutory levies, has been reduced to 6 basis points from an effective 8.59 basis points earlier. For derivative transactions, the net brokerage cap has been reduced to 2 basis points from an effective 3.89.

How significant is the impact?

Sebi’s overhaul of the mutual fund expense framework may change how costs are presented, but it is unlikely to alter how most investors make decisions materially. Market experts point out that long-term investors are generally indifferent to marginal changes in expense ratios, focusing instead on consistency of performance, volatility control and the quality of fund management. A 5–10 basis point reduction in costs rarely influences portfolio choices. For example, if investors are choosing between two flexi-cap funds, one with a largecap tilt and another with greater mid-cap exposure, the decision is still driven by track record and risk management rather than which option is marginally cheaper. As one market expert who spoke with ET Wealth on condition of anonymity puts it, “Lower costs without performance offer little comfort,” adding that the real test for investors remains whether a fund delivers fair value over time.

Clarity or cost reduction?

At the heart of Sebi’s changes is a push for transparency rather than a dramatic cut in what investors pay. Dhirendra Kumar, Founder and CEO of Value Research, says the restructuring improves clarity but does not materially reduce the all-in cost for investors. “Once you carve statutory levies out of the TER and show them separately under the BER framework, the headline number looks lower, but the investor’s total bill doesn’t necessarily fall by the same amount,” he says.

He adds that the genuine savings are likely to be modest. “The real relief comes from two places: removing the extra five basis points that was linked to exit-loadrelated expenses and tightening the ceiling on brokerage and trading costs. Put together, that’s roughly six to eight basis points of genuine cost reduction. That is the real gain for investors,” Kumar says.

BER versus TER

The introduction of BER alongside TER has also raised questions about how investors should track costs in the future. Kalpesh Ashar, Founder of Full Circle Financial Planners and Advisors, urges caution, noting that the concept is still new. “It’s a new concept, and I would like to see how it plays out in practice before taking a strong view,” he says.

Kumar, however, believes the new structure will make comparisons easier if investors read it correctly. “Breaking costs into clearly defined components improves understanding and reduces the scope for confusion,” he says. “But investors must look at BER and TER together, because they move in tandem. If you only look at one, you’ll get the wrong impression.”

Revised expense ratios for equity funds

Bigger impact

While Sebi has positioned the changes as investor-centric, the immediate economic impact is expected to fall more on and brokers. According to a report by Prabhudas Lilladher, reduction in the upper cap of cash brokerage from 8.59 bps to 6 bps and derivative brokerage from 3.89 bps to 2 bps would adversely affect brokers. “Cash revenue might be affected by 15-20% while derivative revenue would be hit by 3-5%,” it said in a report.

Active versus passive

On whether the changes shift the activeversus-passive debate, Kumar sees little impact. “This won’t tilt the balance either way,” he says. “Trading costs are already low, and turnover is often driven by investor flows as much as by the fund’s strategy.”

Ashar also notes that passive funds already operate in a low-cost environment, and while the new caps may help bring down active fund expense ratios, “whether that ultimately reflects meaningfully in NAV performance will only be clear over time.” One area where the reforms fall short, Kumar says, is the limited attention to direct plans. “Direct plans are no longer a niche—they are a major force in the market. Yet the framework still treats them as an offshoot of regular plans, instead of recognising them as a primary category in their own right,” Kumar says.