A new year often brings with it new rules. This January, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) finally cut the red tape that has discouraged UK companies from including DIY investors in their bond issuances for over 20 years.

The new regulation reduces the minimum trade size from the previously prohibitive €100,000 (£87,000) to just £1, and introduces a new bond labelling system, in a huge step forward for accessibility.

The London Stock Exchange’s (LSE) new ‘access bond’ badge will highlight any bond with a target market that includes private investors, which will cover gilts as well as corporate bonds, while its new ‘plain vanilla listed bond’ (PVLB) identifier will help signpost the most straightforward bonds for DIY investors. These bonds must be unsecured, unsubordinated and issued by UK-listed companies.

So as the market anxiously awaits its first PVLB issuance, we take a look at how the purchasing process might work, and what you need to know before buying.

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

How it works

Investors can identify the bonds available to them on the LSE’s ‘Order Book for Fixed Income Securities’ (OFIS) webpage, by searching for the ‘access bonds’ badge, and then looking out for the new PVLB distinction.

In terms of purchasing the bonds themselves, this can either be done through the primary market – though the practicalities of this and the need to trade at speed make it unfeasible for most investors – or (more typically) via intermediaries such as AJ Bell (AJB), Interactive Investor, and Hargreaves Lansdown. These platforms can purchase large blocks of bonds for resale onto individual investors in the secondary market.

You will not need to pay capital gains tax on a sterling corporate bond, providing HMRC designates it as a qualifying corporate bond as is typical. But you will have to pay income tax on the interest received from the bond’s coupon if it’s not held within an Isa.

What to consider

Unlike a bond fund, where the research is conducted by the fund manager, buying individual corporate bonds calls for an elevated level of due diligence. Knowing what you are buying is crucial, so it’s important to do your homework.

Below, we work through the key considerations for investors, step-by-step, using the Vodafone 5.9% 26/11/32 bond (VO32) – one of the very few legacy bonds from 2002 that had accessibility built in.

Understanding the bond contract

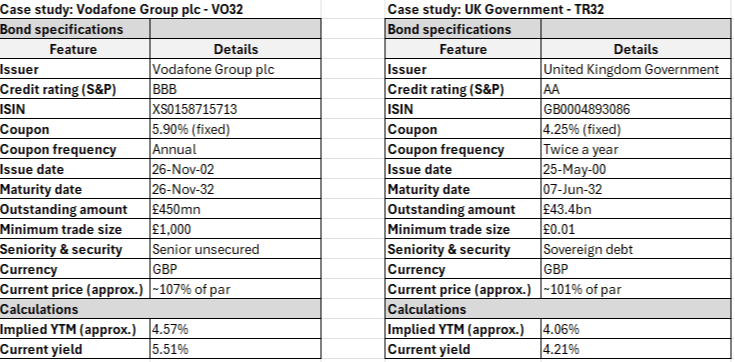

The table below gives the basic specifications of the Vodafone bond, as well as a comparison with a UK gilt of similar maturity – the Treasury 4.25% 07/06/2032 gilt (TR32).

To properly understand a bond contract, it’s important to get comfortable with the basics. The coupon, which for VO32 is 5.9 per cent, means that Vodafone pays £59 in interest for every £1,000 of face value each year until it matures. This is higher than the coupon on the TR32, reflecting the higher level of risk that comes with corporate bonds over gilts.

Duration, ie how long the bond has until maturity, is another important consideration. While VO32 is on the shorter side, maturing in just over six years, longer-dated bonds come with greater interest rate risk and no bond is free from it entirely. The longer the duration, the greater the chance that interest rate cycles will shift. When interest rates rise, fixed-coupon bonds become less valuable and their prices fall. Shorter-dated bonds therefore offer less price volatility.

At the time of writing, VO32 trades at 107 per cent of its face value, or ‘par’, ie it is currently at a premium. This is because the interest rates available on similar bond issuances today are lower, making Vodafone’s 5.9 per cent coupon look generous and increasing the value of the bond. Bond prices move inversely to interest rates and yields.

Finally, the seniority and security of a bond signal the priority that bondholders have in the event of bankruptcy. Creditors holding senior debt get paid first, followed by subordinated debt holders, and finally equity holders. Secured bonds tend to be backed by assets, and are preferable to unsecured bonds that rely on the creditworthiness of the company alone.

Analysing the return profile

To analyse the return profile of the bond, two calculations are important: the current yield, and the implied yield-to-maturity (YTM).

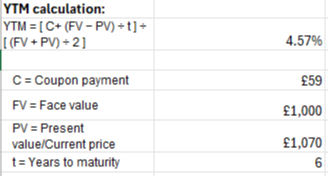

The current yield offers a snapshot of the yearly return, and is calculated by dividing the coupon by the bond’s current market price. For VO32, this means that £59 is divided by £1,070 to generate a current yield of 5.51 per cent. This is more of a short-term, income-focused metric.

YTM provides a longer-term assessment, and represents the total return if you were to buy and hold until maturity. The YTM is iterative, so accounts for all of the interest payments, plus any capital gains or losses depending on whether the bond was bought at a discount or a premium to par (a bond will always mature at its par value, rather than at a discount or premium).

The calculation in the boxout illustrates an easy way to approximate this yield.

The YTM is a handy tool for comparing the returns profile of different bonds with similar maturities. For example, we can see that the difference between the YTMs for VO32 and TR32, known as the ‘spread’, is 51 basis points. This is quite narrow, and while on the one hand it reflects the fact that the market sees Vodafone as not much riskier than the UK government as a counterparty, it also means that for the extra slice of default risk you are taking on, you are not being paid lots more in return.

Investors can also use spreads to compare bonds issued by other companies. If Vodafone’s borrowing spread over gilts was materially wider than its peers, this could be an indicator of more specific market concerns about the company.

Gauging the default risk

Finally, while bond spreads are one way to assess default risk, they are neither the best nor the only way.

Often, specific credit metrics are included as covenants in the bond documentation. These are legal obligations which protect bondholders, such as leverage and interest cover ratios.

A company’s leverage ratio, which is calculated by dividing net debt by earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda), measures how many years of earnings would be required to cover a company’s debt, with anything over four being considered high risk. In Vodafone’s case, the company has a stated target leverage range of 2.25 to 2.75 times.

Interest cover is calculated by dividing Ebitda by a company’s interest expense, and can gauge how comfortably a company is able to cover its interest payments. Companies with less than two times cover tend to be riskier.

Other methods to assess a company’s financial health include checking its free cash flow and its credit rating. A company generating consistently negative free cash flow is a red flag, as this means that the cash it generates after operating costs and capital expenditure may not be enough to cover its payment obligations to creditors.

Meanwhile, credit ratings are provided by agencies such as Moody’s, S&P, or Fitch rate the issuer’s likelihood of default. Issuers rated from AAA to BBB- are considered “investment-grade” and are assumed to have a higher credit quality than those rated BB+ and below, which are sometimes referred to as “junk”.

As with any contract, understanding the terms are key. Once you are comfortable with the duration, coupon, yield on offer and the level of risk you are taking, you should be in a position to accurately assess whether the corporate bond in question is right for your portfolio. Then all that’s left to do is patiently await the first PVLB issuance.