(Bloomberg) — Jimmy Yang believed he was making a boring but safe investment when he bought convertible bonds of China Grand Automotive Services Group Co. in May. The country’s 801 billion yuan ($119 billion) convertible debt market was long an oasis of small but sound returns, providing shelter even during last year’s brutal market downturn.

But by mid-July, the 38-year-old lost half of his 1 million yuan investment as tighter capital market rules led to panic selling in small-cap stocks and their related bonds, including Grand Auto’s.

“I’d told myself it’s safe because it had an AA+ rating,” said Yang, a finance director at a manufacturing company in the southern city of Guangzhou, adding that he’d been emboldened by past investment successes.

He is one of many investors hit by a downturn in China’s equity-linked bonds, a market now gripped by fears of default. This week alone, Bluedon Information Security Technologies Co. and LingNan Eco & Culture-Tourism Co. announced defaults on their convertible bonds. The asset was considered near-zero risk until apparel design company Sou Yu Te Group Co. defaulted in March, the first-ever non-payment of its kind since Chinese companies started issuing such bonds in the 1990s.

While the sum of the defaulted notes so far have totaled under 2 billion yuan, at least 50 bonds worth a combined 58 billion yuan are now trading a 90 yuan or lower, a level indicating stress. The index for Chinese onshore yuan convertible bonds is now down nearly 9% from a year earlier, having fallen for six consecutive trading days since Aug. 8 — the longest losing streak since January.

The woes stand in contrast with enthusiasm in the offshore market over convertibles issued by Chinese tech giants. It may also have consequences beyond the niche asset category, adding to concerns over the health of smaller companies in the world’s second-biggest economy.

“The damage won’t be confined to the convertible bond market,” said Max Dong, partner at Guangzhou JiuYuan Private Fund Management Co., saying he expects a particularly strong impact on smaller firms.

Convertible notes come with fixed returns as well as the option of being converted into equity, usually at a premium.

In the case of Grand Auto, one of China’s largest car dealers, concerns over lackluster car sales and general market gloom had weighed on the company’s shares for over a year. The selloff accelerated in June through early July as investors began to fret over tighter rules on stock market listings. The government in April announced several measures, including broadening the scope for delisting shares, aimed at weeding out weaker firms from the market. For example, it said mainboard-listed companies may be delisted if their market capitalization fell below 500 million yuan for 20 sessions, rather than an earlier 300 million yuan.

Grand Auto shares eventually traded below 1 yuan for 20 straight trading days, triggering a regulatory rule removing such shares from exchanges. The 2.89 billion yuan convertible bond was delisted in July.

“The rules for convertible bonds trading now has entirely changed,” said Zou Shaokun, a fund manager at fund manager at Beijing Eastern Smart Rock Asset Management Co. “Fear is rampant, and it’s causing an avalanche in convertible bonds traded at low prices.”

The stricter listing rules were aimed at boosting investors’ confidence in the market. But they triggered fears among investors of being caught in a selloff and subsequent default. A stock delisting normally leads to the delisting of its related convertible bond. While this doesn’t always lead to default, issuers can face difficulty rolling over maturing debt if funding options are limited — as they often are in China today. Grand Auto did not respond to requests for comment.

“Once delisted, investors basically can only count on issuers to repay the notes as market liquidity quickly dries up, and so they rush to sell, causing a death spiral,” said Deng Hao, founder of Beijing GEC Asset Management Ltd., a Beijing based private fund focused on high-yield bond investment.

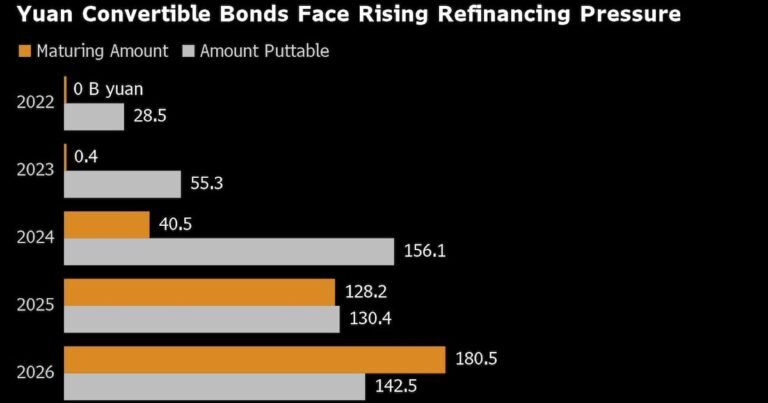

The worst, some say, may be yet to come. Around 258 billion yuan worth in convertible bonds are set to mature or become puttable in 2025 and even more the following year, according to data provided by Ratingdog Shenzhen Information Technology Co.

Broad Impact

The meltdown has led to a decline in issuance in the primary market. Local convertible note sales have shrunk 79% from a year earlier to 15.6 billion yuan in the first half of this year, the lowest level since 2016, Bloomberg-compiled data show.

Smaller firms are also being shunned in the equity market. The CSI 2000 Index, an index tracking the share performance of China’s small-cap stocks, is down 25% year-to-date while blue chips have fallen less than 3%.

As a result, small-cap businesses now face fewer avenues of financing, especially when compared with bigger and state-backed peers which can turn to domestic banks or offshore lenders. This, in turn, may mean weaker investing and hiring by smaller enterprises, which contribute more than 60% to GDP.

Economists say the fallout may also be lasting for China’s investors. Gary Ng, an economist at Natixis SA, said investors were now looking for steady returns amid growing concerns including a real estate crisis and an aging population, but there were few safe choices left.

“There’s basically too much capital wanting to get this sort of stable income, but there just aren’t other options for them,” he said.

Yang, the retail investor who’s now lost a majority of his savings, acknowledges his bet on Grand Auto was foolhardy. He thinks authorities could have done a better job protecting investors like him, but unlike some others who’ve protested over their losses, he’s not optimistic about getting any money back.

“I’ve lost hope,” he said.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.