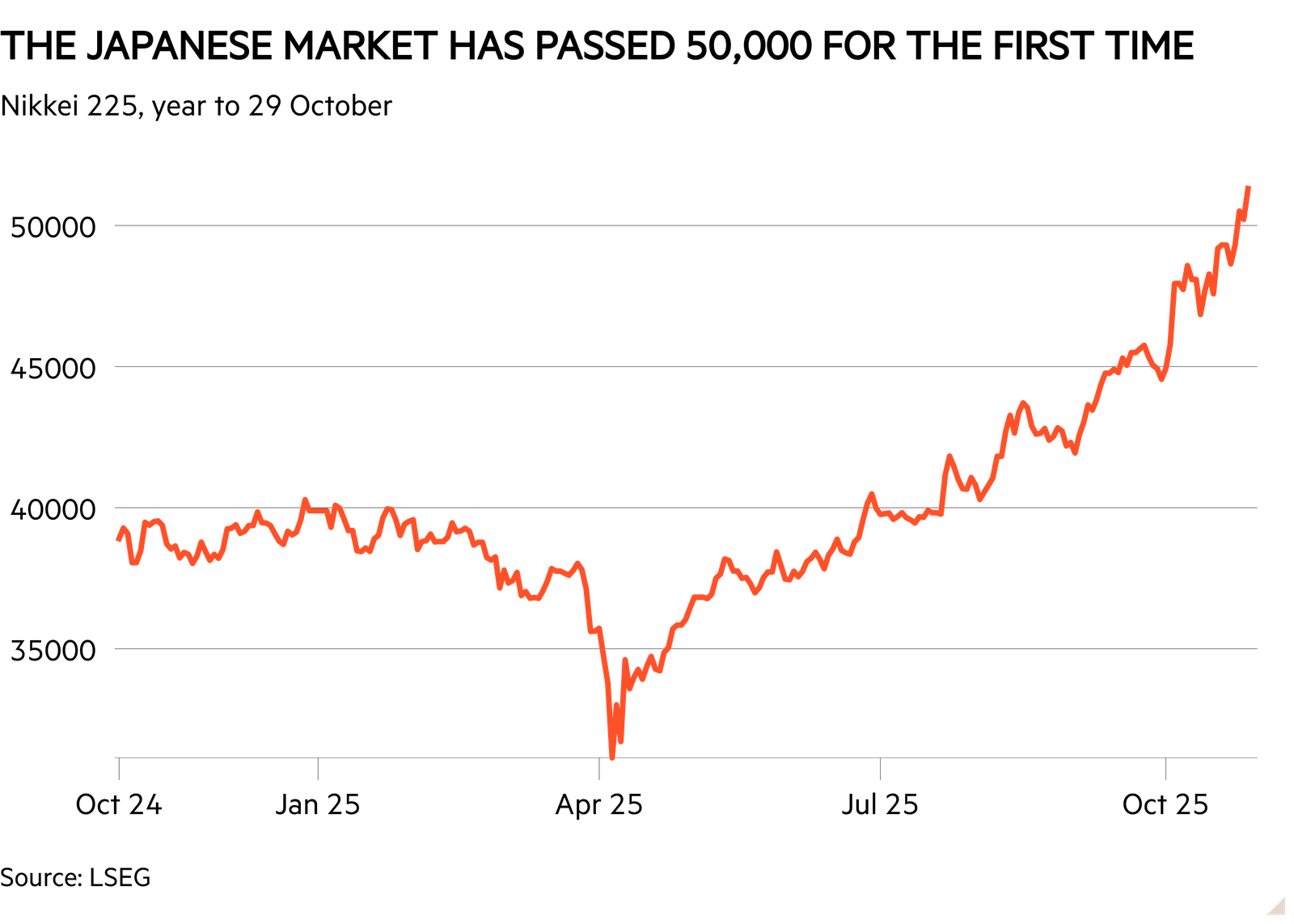

Earlier this month, the Japanese stock market reached a record high, with the Nikkei 225 jumping above the 50,000 mark. From the start of the year to 28 October, the index was up 27.7 per cent in local currency terms and 22.5 per cent in sterling.

A lot of change is afoot in the country. From a political perspective, all eyes are on Japan’s first female prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, elected earlier this month. She is a conservative whose dovish stance on fiscal policy contributed to the market’s rally. Takaichi’s Liberal Democratic party has been in power for years, but her new government relies on a different coalition, supported by right-wing Nippon Ishin, which is expected to look more favourably on defence spending.

Takaichi is in favour of big fiscal spending, at a time when Japan is dealing with an inflation for the first time in decades – core CPI has exceeded the target rate of 2 per cent for the past three years – and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) is expected to hike interest rates. In a country that has had to deal with deflation for years, price growth is arguably a good thing, as long as it doesn’t prove too stubborn. For one thing it could encourage Japanese households, who are sitting on big piles of cash, to consider more investment in the stock market.

That is the theory, at least, and recent performance may encourage more participation. Last year, the Japanese market finally surpassed the levels it had reached at the top of the bubble in 1989, which feels like an important psychological milestone.

Meanwhile the BoJ is slowly bringing rates up to a more conventional level, having hiked twice last year and once in early 2025.

Takaichi’s election could theoretically delay further increases, but it is far from a given. Oxford Economics analysts argue that “market pressures – especially the weakening of the yen – will probably leave her no choice but to accept some rate hikes” and that “persistently high inflation and the cost of living crisis continue to be politically very important, and it will probably become more difficult to justify a continued very low policy rate to the public”.

The main piece of bad news is that over the past two years, the yen has weakened more than analysts had expected, partly driven by interest rates in the country remaining much lower than in the rest of the world. Among other things, this has reduced sterling returns for UK investors – as well as buoying export-focused companies and pushing inflation up.

Still, equity investors are clearly feeling very confident about both the Japanese market and its new prime minister.

The BoJ owns trillions of yen’s worth of Japanese stocks via exchange-traded funds, having tried to stimulate the country’s struggling economy via these purchases in the past. Not even the announcement earlier this year that it would start selling up has really alarmed investors. “The market has taken this in its stride, an indication of the level of investor confidence,” notes Mick Gilligan, head of managed portfolio services at Killik & Co.

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

Long-term drivers

Masaki Taketsume, manager of Schroder Japan Trust (SJG), argues that the rally has been driven by “receding uncertainties”, including signs of progress on US-China tariff talks, easing worries in US credit markets, and the new government’s coalition agreement, which “lowers political risk”. “Valuations now sit at the upper end of historical ranges, so further multiple expansion looks limited near term; the pace of earnings recovery will be key to the rally’s durability,” he says.

A continued rally may partly rely on further progress on long-term trends, particularly corporate governance reforms, which are pushing companies to be better at giving back money to shareholders. “The drive led by the Japan Exchange Group – to make companies more efficient with their capital, improve shareholder returns through dividends and buybacks, and unwind cross-shareholdings – will persist. That’s what ultimately underpins Japan’s equity story,” says Richard Aston, portfolio manager of the CC Japan Income & Growth Trust (CCJI).

Gilligan notes that the return on equity for Japan’s Topix benchmark has risen from below 8 per cent to around 9.5 per cent in recent years. “There is certainly scope for this to improve further, towards the level of other developed markets, which are typically in the 12-15 per cent range,” he says. “The scope for re-rating is even greater among Japanese mid and small caps, many of whom still have high levels of cash on their balance sheets.”

A range of sectors have benefited from the latest economic improvements. “I see opportunities in sectors such as financials, construction, industrials and utilities, which all enjoy steady pricing power as labour shortages, digitalisation and infrastructure demand drive order books, while also having relatively limited sensitivity to US tariff outcomes,” says Min Zeng, manager of the Fidelity Japan Fund (GB00B882N041). He notes that banks in particular have been the clearest beneficiaries, “underpinned by resilient net interest margins, lower credit costs, and progress in cost controls”.

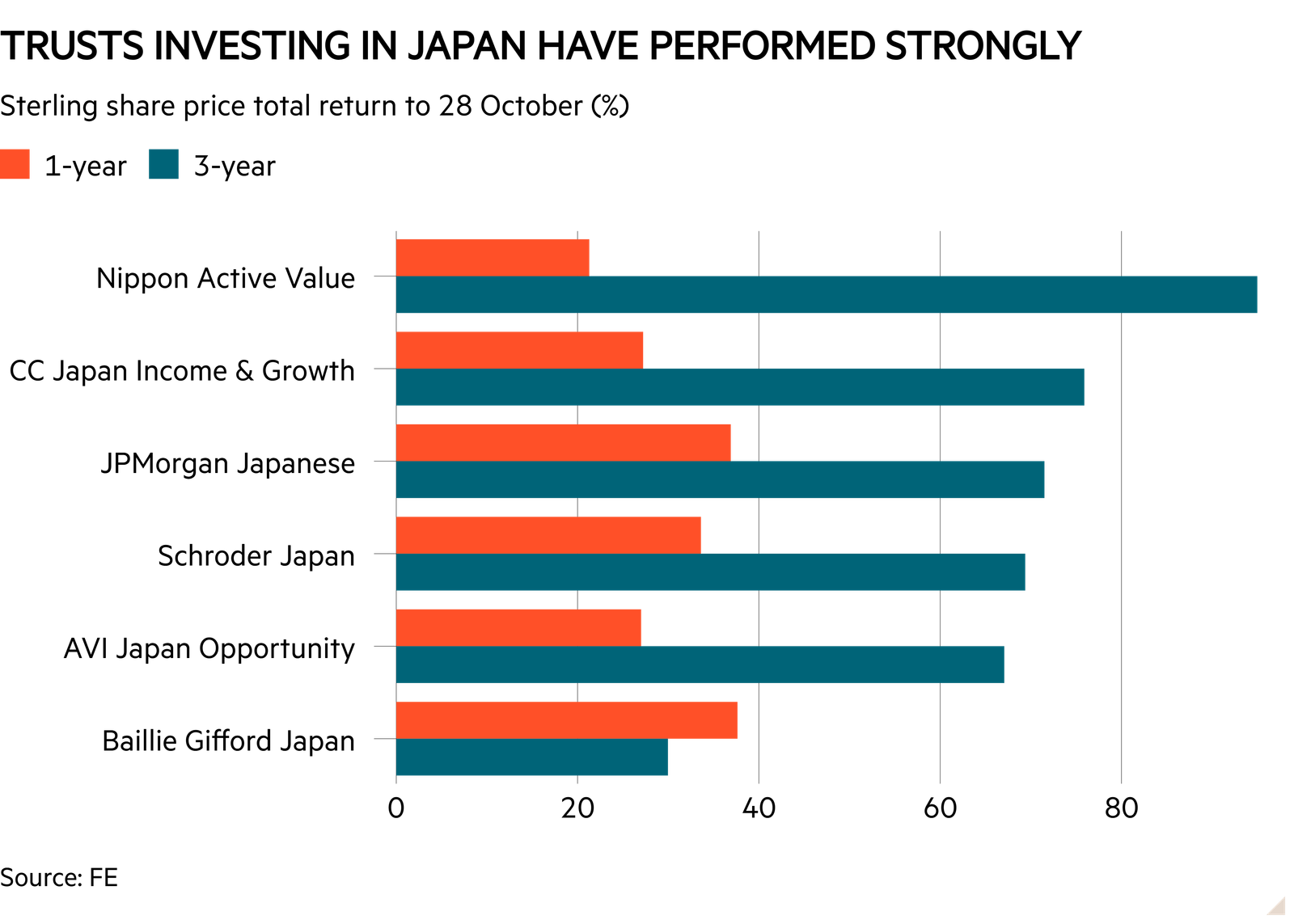

Investors who want to tap into Japan’s market have a wide range of funds and trusts to choose from. On the smaller companies front, AVI Japan Opportunity (AJOT) and Nippon Active Value (NAVF) deploy an activist, value approach which relies on engagement with its company holdings. It has been working well in combination with the market’s corporate reforms. Both are fairly concentrated, with the top 10 holdings accounting for 85.5 per cent of the former portfolio and 71.4 per cent of the latter as at the end of September.

As for large-caps, value funds have been outperforming in the past five years. Among investment trusts, one option is Schroder Japan, which has a value tilt and looks for undervalued companies where a catalyst for improvement is apparent.

CC Japan Income & Growth’s quality investing approach has also had a very strong five years. The trust seeks to combine rising dividend streams with capital growth and currently offers a yield of 2.4 per cent. Schroder Japan promises a bigger payout of 4 per cent of NAV, which was introduced last year, but how much that amounts to in monetary terms ultimately just depends on performance.

Among open-ended funds, the IC Top 50 Funds list includes Man Japan CoreAlpha (GB00B0119B50), whose value approach has been doing extremely well. Away from the list, one interesting if small option is JK Japan (IE00BJBY7B30), which claims to look for “quality companies, combined with an acute eye on valuation metrics” and to “blend top quality value and growth companies”. The fund has been another standout performer since its launch in early 2020. In the five years to 22 October, both of these funds returned roughly 134 per cent.

Interestingly, growth funds have also been showing signs of life this year after a prolonged period of poor performance. Baillie Gifford Japan (BGFD) has returned 31.8 per cent in the year to 21 October, although it still has quite a lot of underperformance to make up for from previous years.

The trust is currently focused on the themes of artificial intelligence and automation. The portfolio construction process looks in some ways similar to that of global equity stablemate Monks (MNKS), in that it divides the portfolio into different types of growth companies.

For Baillie Gifford Japan, these are secular growth (54.8 per cent of the portfolio as of March), in other words companies with the opportunity to grow rapidly but where there’s more risk; growth stalwarts (17 per cent), where growth is less rapid but more predictable; and then ‘special situations’ (13.9 per cent) and ‘cyclical growth’ companies (14.3 per cent).

Fidelity Japan (FJV) is also doing very well this year, but after failing a continuation vote is in the process of being merged into AVI Japan, with shareholders facing a choice between a cash exit or having to accept a fairly radical shift in strategy.