Investors considering funds that invest in private assets must pay closer attention to something mutual funds and exchange-traded funds have taught them to take for granted: liquidity, or the ease with which they can buy and sell.

Most semiliquid funds, including interval funds, offer investors access to harder-to-trade and potentially higher-returning assets like private credit and private equity but restrict redemptions to tightly controlled repurchase windows. This allows the funds to invest in illiquid securities without worrying about redemption surges forcing them to sell holdings at fire-sale prices in downturns or panics, while giving investors periodic redemption opportunities.

This article looks at some real scenarios that show that the liquidity of semiliquid funds can become even more limited in tough times. When new money stops coming in, managers may restrict or suspend withdrawals to avoid selling assets at inopportune times. This move, though, often erodes investor trust and signals serious trouble for the fund.

Take non-listed REIT funds, for example. In 2022, rising interest rates pressured real estate valuations and liquidity. The Morningstar US Real Estate Index, which tracks listed REITs, dropped more than 25%, widening the gap between listed REITs and non-listed REIT funds, which typically are slower to update valuations in reaction to market shifts.

What Can Go Wrong?

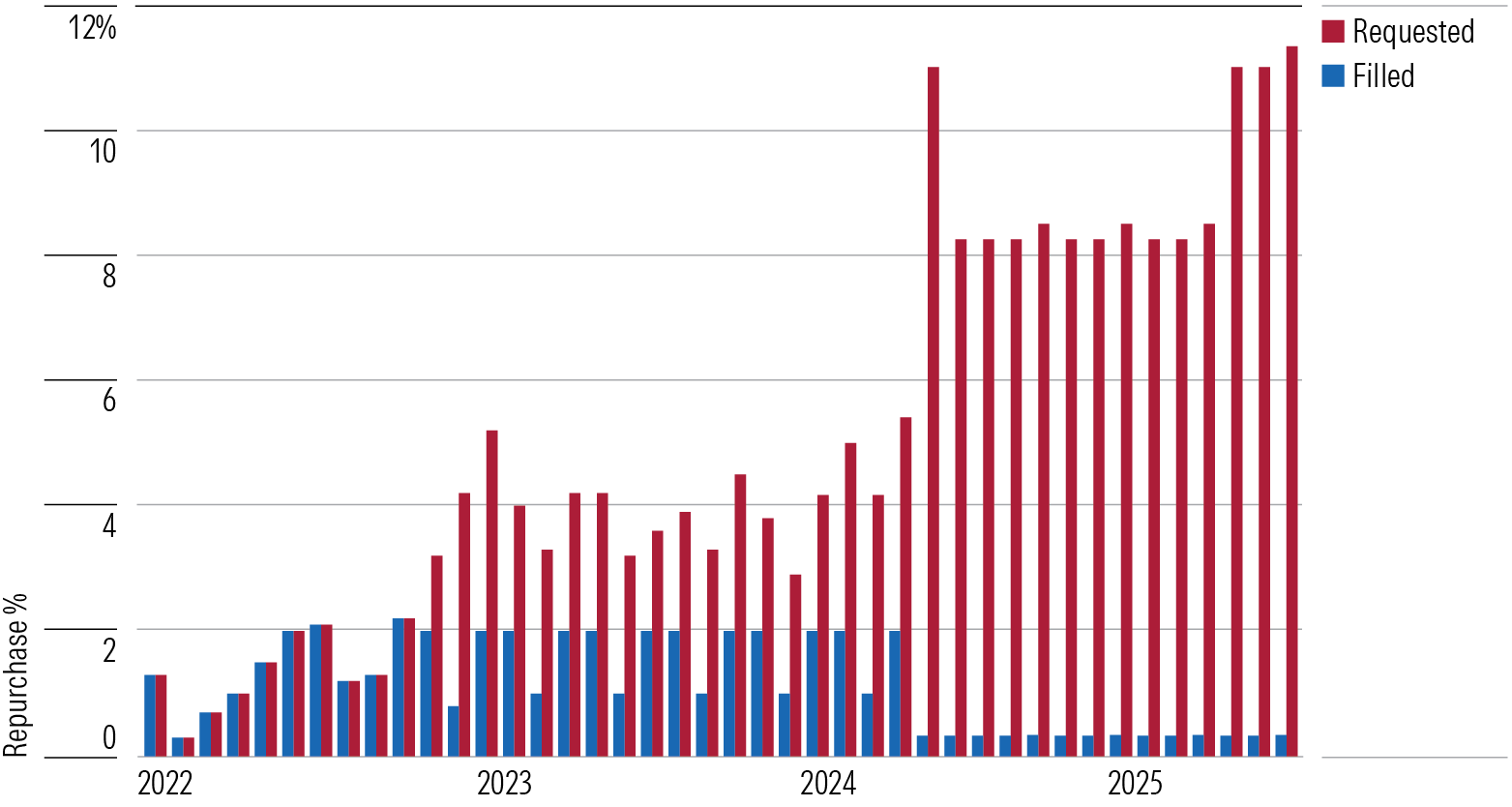

Since then, Starwood Real Estate Income Trust investors haven’t had a good experience. Starting in late 2022, SREIT investors received only part of the amount they requested because investors wanted to withdraw more money than the fund allowed. Investors received less than half the cash they requested in 2023, and the manager had to borrow more than $1 billion to do so.

In May 2024, Starwood sharply reduced the number of shares it repurchases each month to 0.33%, with a quarterly limit of 1.0%, and cut its base management fee by 20%. Still, in late 2024 and through 2025, the manager had to resort to asset sales to bolster liquidity to continue to meet redemptions, and investors continued to receive a fraction of the liquidity requested.

Bluerock Total Income+ Real Estate Fund is also facing pressure as more investors ask to withdraw money. To address this, the fund wants to change from an interval fund to a closed-end fund that trades on the New York Stock Exchange. Currently, investors can sell their shares back to the fund at a price set by the manager. If the change is approved, investors would have to sell their shares on the open market, where prices could be lower. This means investors, not the manager, would take the loss if the market values the fund’s assets below the manager’s estimate.

It’s Not Just Real Estate

Other asset types have also struggled when too many investors tried to withdraw money at once. The Wildermuth Fund, an interval fund that invests in private companies and startups, began facing material redemption requests in 2017. In 2020, the fund delayed its payout deadline after problems valuing some of its harder-to-sell investments caused an audit delay.

The fund muddled along for a while, but the covid pandemic made it harder to raise new money, even as investors kept asking to cash out. Tighter capital markets made exits harder for private companies in 2022-23, while valuations also fell significantly.

By June 2023, the fund’s shrinking size made it unsustainable. The board decided to stop all new investments and withdrawals and start selling assets to close the fund. So far, investors have not received any payouts. Selling these harder-to-value assets takes time and can be expensive, especially when the fund is under pressure to sell. The fund has suffered significant declines since the windup process began but hopes to start returning money to investors in late 2025.

Who’s Passed the Liquidity Crunch?

Semiliquid funds can survive liquidity events, but it can be a testing experience. In 2022, investor requests to withdraw money from Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust increased, peaking as the year closed and into 2023. As shown in the next exhibit, BREIT allowed investors to cash out 2% each month, up to the maximum 5% per quarter. But this was significantly less than the investors requested—by December 2022, the fund could only meet 4% of total withdrawal requests because it had already hit its quarterly limit.

In 2023, BREIT continued to let investors cash out 5% of shares each quarter, but this covered about a third of what investors wanted. BREIT was running out of liquidity as more investors tried to exit. In January 2023, The University of California endowment invested $4 billion in BREIT on the proviso that it receives a minimum annual return of 11.25% over six years. It wasn’t until the second half of 2024 that withdrawal requests eased and the fund’s situation stabilized.

How Can I Get My Money Back?

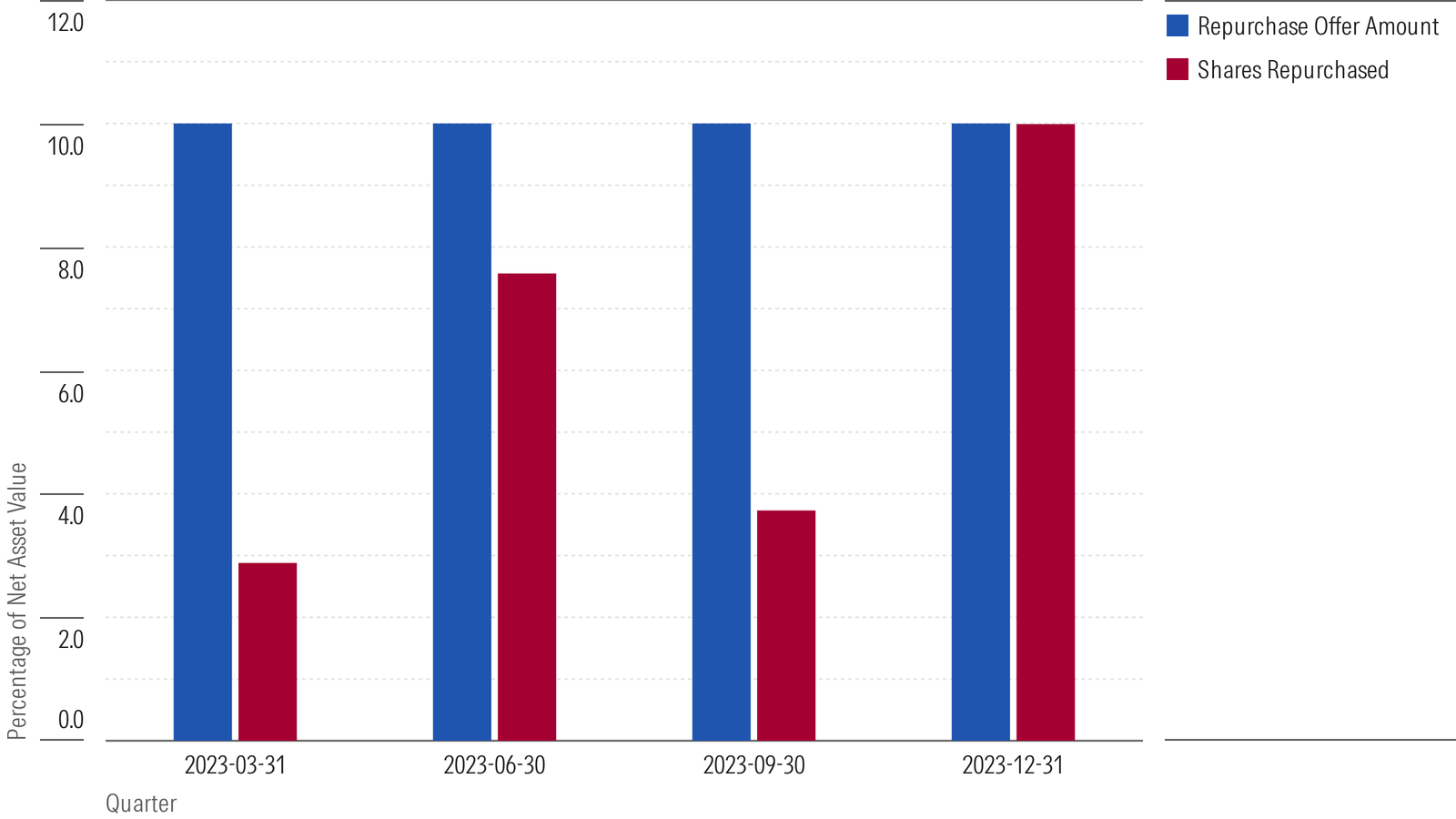

There are positive examples, however. Sometimes semiliquid funds offer more liquidity than the minimum required. For example, rules says an interval fund must offer to buy back at least 5% of its shares at each interval, but the fund’s board can choose to allow more—up to 25%—which the fund announces ahead of time. Pimco Flexible Municipal Income Fund, for instance, has let investors cash out 10% of the fund’s shares in several recent periods, as shown in the next exhibit. However, investors shouldn’t rely on this extra liquidity; what is given can be taken away.

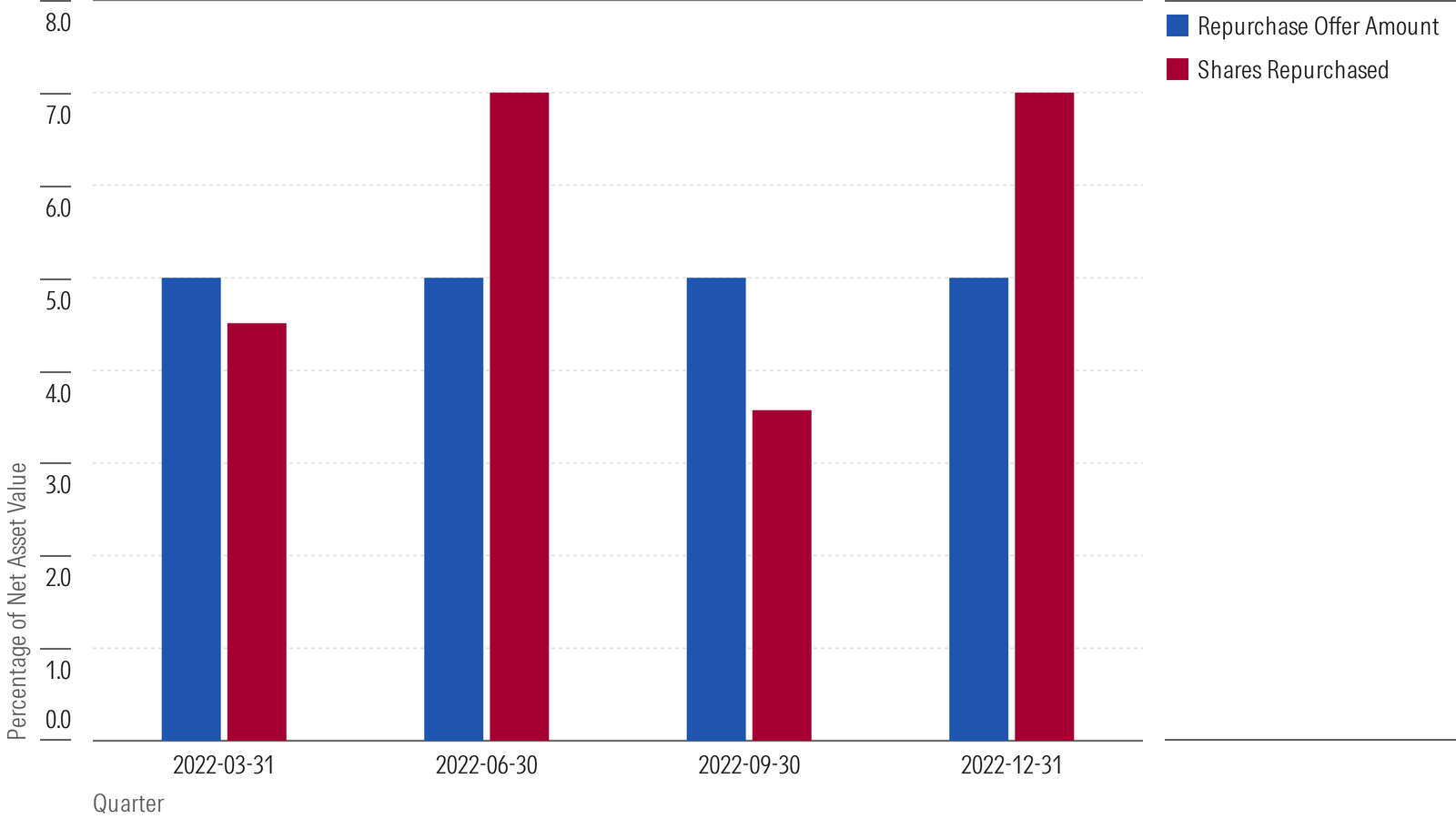

The Private Shares Fund invests in private companies that are close to going public. When many investors want to withdraw money at once, the fund can choose to let people cash out more than the minimum required, up to a maximum 2% extra.

For example, in the second and fourth quarters of 2022, and also in the second quarter of 2020, the fund allowed extra withdrawals when requests were high—especially as rising inflation, interest rates, and the covid market downturn made investors wary of high-growth companies.

However, once investors start withdrawing from a fund, it can be hard to slow the trend. If new money coming in doesn’t match the amount going out, the fund could have to resort to selling investments to pay those who want to leave. Since 2022, the fund has regularly faced requests from investors to withdraw 5% of its assets each period.

A Way to Help Investors

Funds could do more to make information clear and accessible. While they announce when and how much investors can withdraw, it is difficult to find out how much money was actually paid out in each period. Investors must piece together this information from various regulatory documents, which are rarely straightforward or consistent.

Knowing how much investors are withdrawing, especially as a percentage of the fund’s total value, is key to understanding a fund’s stability and investor sentiment. Yet, this data is usually missing from fund websites and is not presented in a way that makes it easy to compare funds or spot trends. Clearer and more consistent reporting would help investors.

What Should Investors Be Aware Of?

Apart from the cases above, most funds that limit how often investors can withdraw money have avoided a liquidity crunch. Funds started in 2023 or 2024 are still new, though, and have not faced a long, severe downturn. The covid-19 shock in early 2020 briefly made it harder for investors to get their money out, but government support quickly eased the situation. And most of today’s semiliquid funds were not around then or for the 2022 downturn.

Furthermore, many investors are encountering these funds for the first time and may not be familiar with how they work or how hard it can be to get money out. If markets get rocky, these investors might react differently than semiliquid fundholders have in the past, leading to unexpected withdrawal patterns.

It’s important to stay organized and plan ahead. Missing a chance to withdraw could mean waiting another three months or more. Think carefully about when you might need your money, and pay attention to market changes that could spur people to cash out. Liquidity matters most when you need it, so don’t get caught off guard.